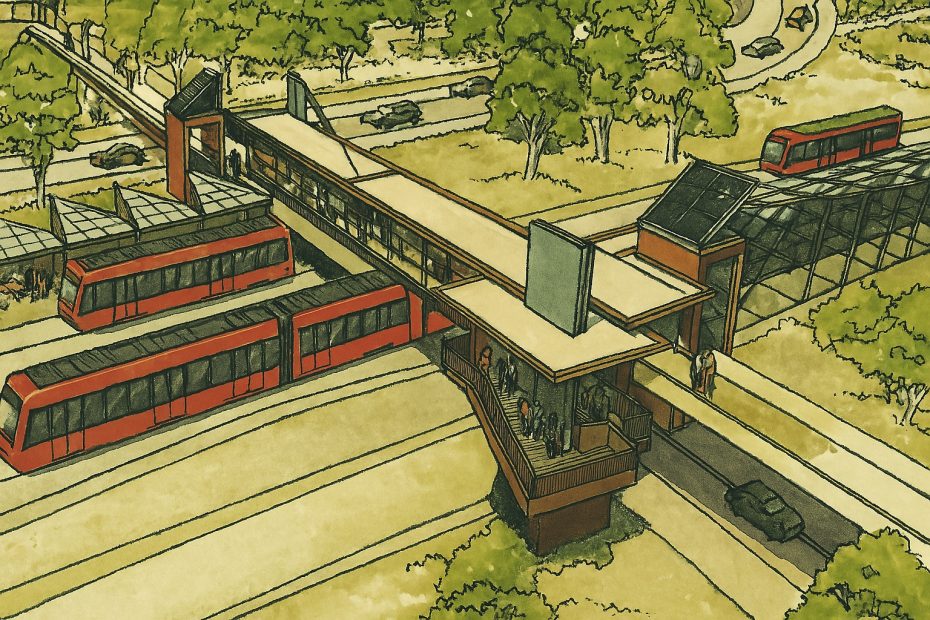

AI Generated Image of Light Rail (Tram) operations on Liverpool to Parramatta Transitway (instead of bus)

The T80 Liverpool–Parramatta Bus Transitway, once seen as a cost-effective and flexible alternative to light rail, is no longer fit for purpose. When developed in the early 2000s, its design reflected the priorities of its time: keeping costs low and maintaining network agility through buses. However, the evolution of Western Sydney in the past two decades—with explosive population growth, increased traffic congestion, and growing demand for sustainable and high-capacity public transport—means the original assumptions from 1998 are outdated. A fixed light rail system is now the most appropriate response to the region’s changing needs.

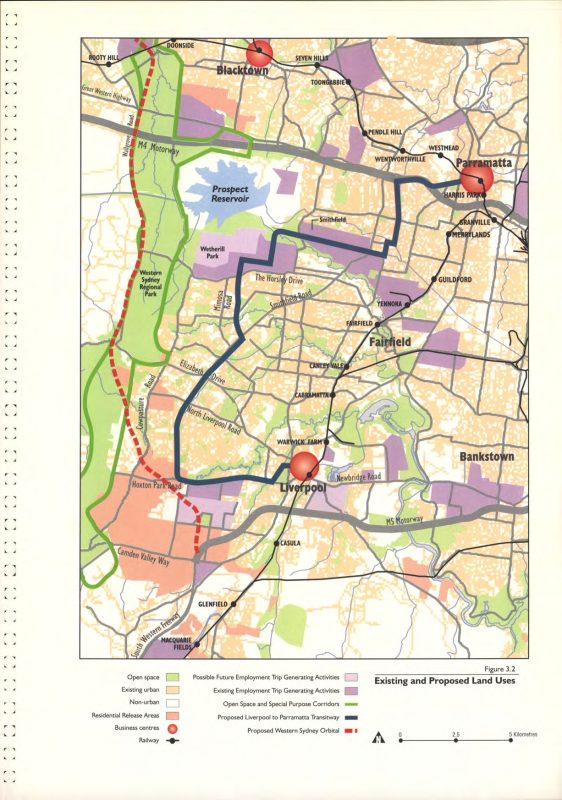

The four LGAs that make up the T80 corridor—Liverpool, Fairfield, Cumberland, and Parramatta—have experienced population surges that far exceed original forecasts. In 2025, the combined catchment is over 1.2 million residents, and this figure is expected to rise by up to 50% by 2041. High-density development in Bonnyrigg, Merrylands, and South Wentworthville, combined with the regional draw of Parramatta and Liverpool CBDs, underscores the corridor’s need for a scalable, high-capacity transit solution. Light rail, unlike buses, can deliver long-term reliability and encouraging land-use transformation.

Car dependency across the corridor remains unacceptably high, particularly in outer suburbs like Smithfield, Bonnyrigg Heights, and Hinchinbrook, where over 60% of households own two or more vehicles. This trend indicates a systemic lack of effective public transport alternatives. Light rail offers a sustainable response: it provides fast, high-frequency service that supports modal shift, reduces road congestion, and improves environmental outcomes. Buses, while important, have proven insufficient in attracting car users or supporting large-scale behaviour change toward public transit use.

Socio-economic disadvantages are deeply embedded in many communities along the corridor. Suburbs like Miller, Cartwright, and Merrylands West consistently rank low on the SEIFA Index, indicating higher levels of unemployment, lower education attainment, and reduced access to opportunities. A fixed light rail service would level the playing field by providing affordable, fast, and direct access to major employment hubs, hospitals, TAFE campuses, and retail centres—without relying on car ownership or multi-transfer bus journeys. This makes light rail a powerful tool for social equity and economic inclusion in Western Sydney.

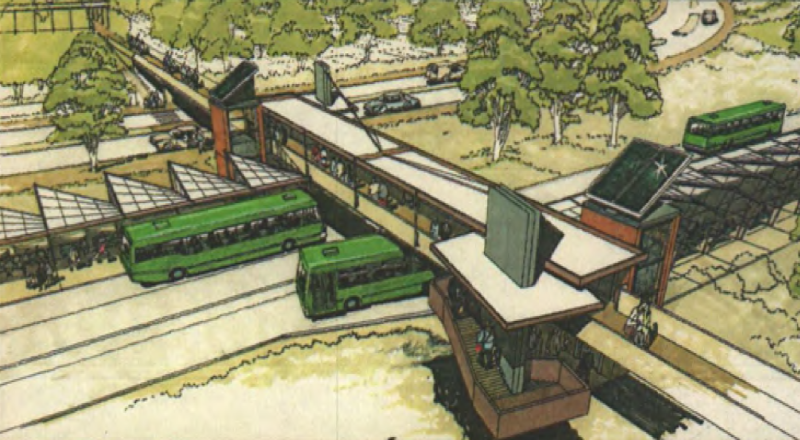

The strategic value of the corridor has significantly increased since 1998. It now connects two declared Metropolitan City Centres—Liverpool and Parramatta—and traverses’ major regional destinations such as Prairiewood Town Centre, Wetherill Park industrial lands, and Bonnyrigg’s urban renewal precinct. With links to multiple heavy rail lines, the future Metro West, and existing bus networks, the corridor offers ideal conditions for intermodal integration. This makes it well-suited for light rail, which functions best as the high-capacity trunk of a multimodal transport network.

The opportunity cost of inaction is rising. The T80 corridor is at risk of being left behind other parts of Sydney that are receiving rail upgrades and Metro connections. Without a major transit uplift, Western Sydney’s growth will increasingly translate into car dependency, longer commutes, and worsening inequality. Light rail is no longer a speculative investment—case studies from Newcastle, Gold Coast, Canberra, and Sydney CBD show it is a proven and effective solution for corridors of similar length, density, and purpose. Liverpool–Parramatta should be next.

Rebuttals to 1998 Light Rail Objections

- Light rail is too expensive (1998)

In 1998, light rail was deemed too expensive when compared to the lower capital costs of buses. While the initial cost per kilometre for light rail remains higher—typically ranging from $80 to $120 million—this view neglects critical lifecycle and value capture considerations. Trams last over 30 years, compared to the 12–15 years of buses, and carry significantly more passengers per trip. Additionally, light rail stimulates land value uplift, with Newcastle’s 2.7 km light rail demonstrating a 13% increase in surrounding property values and $500 million in private sector investment. When amortised over time and weighed against long-term operational savings, modal shift benefits, and development returns, light rail proves economically sound and fiscally responsible.

- Buses are more flexible (1998)

The perceived advantage of bus flexibility has led to a fragmented transport landscape in Western Sydney, with route changes undermining long-term planning and reducing reliability for passengers. By contrast, light rail’s permanence gives certainty to developers and local governments, attracting investment and supporting consistent commuter behaviour. Studies from the Sydney Metro have shown that fixed rail lines generate up to 50% higher development yields than comparable bus corridors. Flexibility, while valuable for coverage, comes at the cost of economic stability and spatial coordination.

- Demand was too low (1998)

Ridership projections in the 1990s significantly underestimated the growth of Western Sydney. As of 2025, the T80 corridor exceeds 20,000 daily passenger boardings, with some peak services experiencing overcrowding. Population forecasts show that over 400,000 new residents will settle in Liverpool, Fairfield, and Cumberland LGAs by 2041. With this scale of growth, the corridor demands a high-capacity, reliable transit mode. Light rail offers the scalability and efficiency that buses can no longer provide, especially during peak-hour demand across major centres like Bonnyrigg, Merrylands, and Liverpool.

- Buses meet future needs (1998)

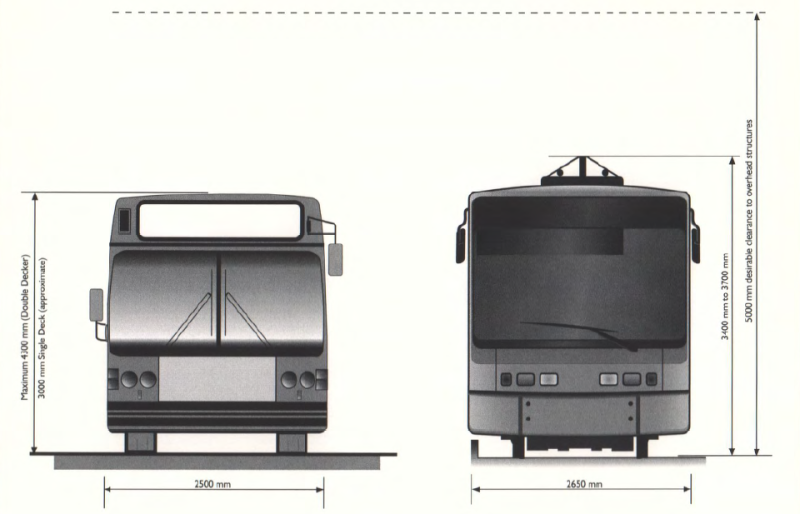

Although buses provide important coverage and frequency, they are not equipped to meet long-term, high-volume demand. Buses require more drivers, are affected by road congestion, and emit more carbon. Trams can carry 250 or more passengers—triple the capacity of a standard bus—with smoother, quieter rides and no tailpipe emissions. In a labour-constrained and environmentally sensitive future, light rail offers a superior operational and environmental profile. The T80’s own success is outgrowing its bus infrastructure, necessitating a step-change in mode.

- Construction is too disruptive (1998)

While construction was once a major deterrent, modern light rail projects use modular track systems and staged implementation to minimise disruption. The T80 corridor already runs largely along grade-separated and dedicated alignments, reducing the complexity of conversion. Projects such as Parramatta Light Rail Stage 1 have pioneered night-time and off-peak works, ensuring minimal interference with road users and businesses. Local communities are also increasingly supportive when disruption is managed transparently and delivers long-term gain.

- Incompatible with traffic (1998)

A major strength of the T80 corridor is its dedicated busway design, making it uniquely suited for conversion to light rail. Where traffic intersections exist, they can be managed with signal priority, as is successfully done in Gold Coast’s G:link and parts of the Sydney CBD line. Unlike retrofitting light rail onto congested city streets, the T80 corridor offers a largely unobstructed pathway—ideal for low-friction light rail operation with minimal new land acquisition.

- Light rail doesn’t drive land use (1998)

Recent Australian light rail projects have shown dramatic impacts on local land use. The Canberra Metro stimulated more than $500 million in nearby development approvals, while Gold Coast’s G:link drove retail, residential, and tourism investment. The permanence and amenity of rail attracts long-term development interest. The T80 corridor—especially areas like Prairiewood and Smithfield—has not experienced comparable uplift under bus operation, underscoring the need for a more catalytic mode.

- Land use too low density (1998)

In 1998, much of the corridor was indeed lower density. But in 2025, Bonnyrigg is undergoing a significant urban renewal, Parramatta is a high-rise city, and infill density is increasing in Merrylands, South Wentworthville, and Cartwright. The corridor also traverses employment zones such as Wetherill Park and Prairiewood, home to large logistics and commercial activity. Land use is no longer an obstacle—it’s an opportunity for transit-oriented development.

- Corridor not strategic (1998)

Today, the corridor is one of the most strategic in NSW, linking two Metropolitan City Centres and serving as the spine of Western Sydney’s future east-west transport axis. The NSW Government’s Future Transport Strategy identifies this corridor as critical to addressing network gaps, congestion, and equity. It intersects housing, education, employment, and health precincts—the ideal profile for a high-capacity fixed transit investment.

- Poor integration with Sydney Trains (1998)

Light rail along the T80 corridor would connect directly to Sydney Trains’ T1, T2, T3, T5 lines via Parramatta and Liverpool stations, and future integration with Metro West enhances this further. With multimodal hubs already operating at both termini, the proposed light rail would act as the high-frequency backbone connecting suburban catchments to the broader Greater Sydney rail and bus networks.

- High tram and depot costs (1998)

Tram fleets do require larger upfront investment, but amortised over a 30+ year life, the per-passenger cost is often lower than buses. Modern vehicles such as CAF Urbos and Alstom Citadis trams offer strong performance, accessibility, and energy efficiency. Newcastle’s five tram fleet services 2.7 km at high reliability, proving that modest fleets can still be effective. Depots can be co-located with maintenance yards or repurposed from underused land along the corridor.

- Low benefit-cost ratio (1998)

Earlier cost-benefit assumptions ignored co-benefits. Emissions reductions, land value uplift, congestion savings, and social access dramatically raise light rail’s real-world BCR. Newcastle’s BCR approached 1.2 and Canberra’s was higher once co-benefits were included. Given the population served, the mode shifts achievable, and land development potential, a Parramatta–Liverpool line could exceed a BCR of 1.4, meeting Infrastructure Australia’s thresholds for funding.

- Buses better for equity (1998)

While buses reach disadvantaged areas, they don’t always meet their needs. Trams provide a fixed, legible, and high-quality service that low-income residents can rely on. Suburbs like Cartwright and Miller lack rail options and suffer from unreliable bus service. Light rail would connect them to jobs, education, and health services—reducing isolation and improving life outcomes while maintaining low fares and full accessibility.

- No travel time benefit (1998)

Light rail vehicles offer faster boarding, acceleration, and signal priority at intersections. Studies show travel from Liverpool to Parramatta could decrease from 45–50 minutes (bus) to 30–35 minutes (tram). This is not just a time saving—it also improves reliability and encourages riders who would otherwise avoid public transport due to unpredictability.

- No Australian precedent (1998)

Since 1998, Australia has developed successful light rail systems in Sydney CBD, Newcastle, Canberra, and Gold Coast. These services operate in a range of urban environments and have demonstrated strong public uptake, land use impact, and operational viability. With these precedents, Western Sydney is no longer experimenting—it is catching up.

It’s time to transform the 🚍 T80 Liverpool to Parramatta route into a 🚈 modern light rail line – and extend the network from Liverpool CBD to the ✈️ Western Sydney International Airport and 🏙️ Bradfield (Aerotropolis).

Sign the petition for light rail in South West Sydney at https://actionnetwork.org/letters/light-rail-for-south-west-sydney-liverpool-to-western-sydney-airport-liverpool-to-parramatta