The Decision That Will Shape Australia for a Century

Australia stands at a generational crossroads in national transport policy. The Australian High Speed Rail Authority’s Sydney–Newcastle proposal is not simply another large infrastructure program competing for funding. It is the foundation of a transport system that will shape Australia’s economic geography, labor markets, urban form, energy consumption, and environmental performance for at least the next hundred years. Very few policy decisions carry consequences of this scale, duration, and irreversibility.

If designed with discipline and built to true global standards, the Sydney–Newcastle corridor can anchor a national network that finally delivers Australia the connectivity, productivity and resilience seen in the world’s leading economies. If, however, the corridor proceeds under its current design assumptions, Australia will lock in a railway that is slower, more expensive, and more constrained than necessary — and the opportunity to correct that mistake will vanish the moment construction begins.

History shows that once the geometry of a major railway corridor is fixed, its performance ceiling is fixed as well. The importance of getting the first corridor right therefore cannot be overstated.

High-Speed Rail Is Defined by Infrastructure, Not Rollingstock

In every country that has successfully delivered high-speed rail, performance is governed not by marketing language or the theoretical capability of rollingstock, but by four fundamental engineering determinants: alignment geometry, sustained operating speed, station spacing and the long-term preservation of those characteristics under heavy daily operation. These parameters are chosen deliberately and protected relentlessly.

China’s Beijing–Shanghai line, France’s Paris–Lyon TGV corridor, Japan’s Tokaido Shinkansen and Spain’s Madrid–Barcelona AVE do not merely reach high speeds occasionally. They sustain extremely high commercial speeds because their alignments are uncompromising: exceptionally large curve radii, long transition lengths, minimal tunnelling, extensive surface and viaduct construction, and complete segregation from slower traffic. The result is average operating speeds in the 280–350 km/h range, maintained reliably for decades.

The Sydney–Newcastle corridor, as currently proposed, violates these principles at a structural level.

The Tunnel-Dominated Design That Guarantees Mediocrity

Under the current concept, approximately 115 kilometres of the 194-kilometre Sydney–Newcastle corridor would be constructed in tunnel — a proportion without precedent in the first stage of any modern high-speed rail system. This single design choice establishes a hard ceiling on achievable performance.

Long tunnels impose multiple interacting constraints on safe train operation. Aerodynamic pressure waves and micro-pressure effects limit speed to protect passenger comfort and tunnel structure. Heat dissipation and ventilation capacity restrict sustained traction power. Emergency evacuation requirements impose conservative braking envelopes and geometric compromises. Fire-safety and rescue access standards further constrain tunnel cross-section and permissible operating conditions.

Collectively, these factors reduce safe operating speeds across large parts of the corridor — particularly south of the Central Coast — to approximately 200 km/h, far below the headline design speed of 320 km/h. This means that while Australia may purchase trains capable of global-class performance, the infrastructure will prevent them from using that capability for most of the journey.

A railway whose dominant operating environment is underground cannot achieve world-class average speed. The physics alone forbids it.

Australia’s Global Standing If Built as Proposed

| Corridor | Tunnel Share | Typical Sustained Speed |

| Beijing–Shanghai | ~5% | 300–350 km/h |

| Paris–Lyon | ~4% | 300–320 km/h |

| Tokyo–Osaka | ~9% | 285–320 km/h |

| Madrid–Barcelona | ~6% | 300+ km/h |

| Sydney–Newcastle (proposed) | ~59% | ~200 km/h over large sections |

No nation has ever launched a flagship high-speed corridor with such an extreme reliance on tunnelling. The reason is simple: tunnel-heavy alignments generate the highest construction cost, the highest schedule risk, the highest maintenance burden and the lowest sustained performance of any design option.

The XPT: When Advertised Speed Collides with Reality

Australia has already lived through this mistake. When the New South Wales XPT entered service in the early 1980s, it was promoted as a revolution in Australian intercity travel. The rollingstock was capable of 160 km/h, an enormous improvement by local standards. Demonstration runs achieved those speeds, and the marketing reflected that capability.

But the supporting infrastructure — track curvature, signalling systems, shared corridor conflicts, maintenance regimes — was never upgraded to match the train. As a result, real-world average operating speeds remained modest, reliability suffered, and the promise of true high-speed intercity travel was never realised. The public perception of speed was driven by the train’s specification; the lived experience was governed by the track.

The lesson could not be clearer:

Speed advertised is meaningless if the corridor cannot sustain it.

Australia is now repeating the same error at national scale.

Sydney Metro: The Cost of Redefining “World-Class”

Sydney Metro offers a second cautionary tale. By Australian standards it represents a major advance. By global metro standards it is restrained: long station spacing, constrained interchange design, limited peak throughput, development-driven alignment decisions and operational patterns that prioritise property outcomes over transport performance.

The project has delivered a functional network. But it has also normalised a dangerous practice: lowering international standards while retaining international language. Once this cultural pattern takes hold, it becomes extraordinarily difficult to reverse.

High-speed rail now risks suffering the same fate.

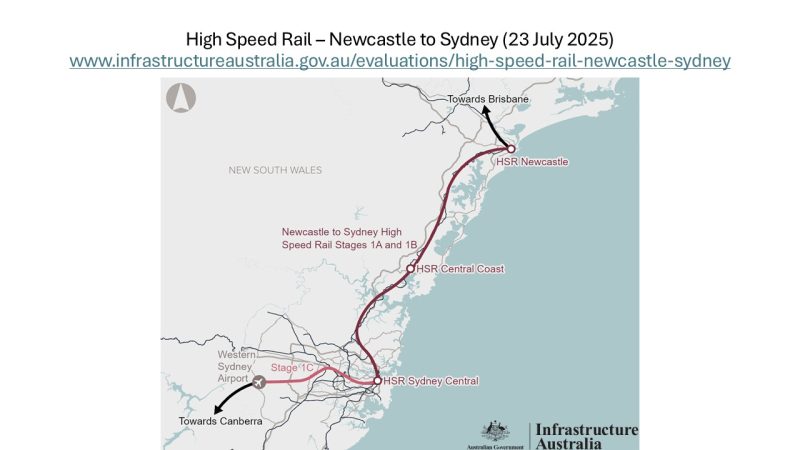

Stage 1A & 1B: Locking in National Underperformance

Stage 1A (Newcastle–Central Coast) and Stage 1B (Central Coast–Sydney) do not merely represent the first segments of the national high-speed rail network; they define the fundamental engineering DNA of the entire system. The geometry, construction philosophy, performance envelope, maintenance regime, and operational culture established here will be inherited by every subsequent corridor built across the continent.

In successful high-speed rail nations, the first corridor is deliberately designed to be the fastest, cleanest, simplest, and most efficient railway the country will ever construct. It becomes the benchmark against which all future lines are measured. It establishes credibility with the public, with investors, with operators and with international partners. It proves that the country understands what high-speed rail actually is.

Australia is doing the opposite.

By embedding extreme tunnel dependence, constrained geometry and suppressed operating speeds into Stages 1A and 1B, Australia is permanently lowering the ceiling of its national network. Once these corridors are built, the system will carry their compromises forever: slower travel times, lower capacity, higher operating costs, reduced timetable flexibility, and diminished economic return on every dollar invested.

The damage is not localised. Every future corridor branching from this spine will inherit its design logic, its standards, and its limitations. Underperformance in the first stage does not stay in the first stage — it propagates across the entire network for generations.

The tragedy is that this outcome is entirely avoidable.

Stage 1C: A Strategic Misalignment

Stage 1C, the proposed extension from Sydney Central to Western Sydney International Airport, compounds the structural error embedded in Stages 1A and 1B and introduces a second layer of long-term network dysfunction.

This alignment duplicates the core function of Sydney Metro West and the future metro airport corridor, creating two parallel high-capacity rail investments competing to serve the same strategic purpose. The duplication of corridors is not merely inefficient — it creates long-term operational complexity, fractured passenger flows, unnecessary capital expenditure, and escalating lifecycle cost.

Worse, the decision to anchor the national high-speed rail system at Sydney Central forces enormous additional tunnelling beneath one of the most complex underground environments in the country. Sydney Central is a terminal geometry designed in the 19th century for steam-era railways. It is structurally incapable of accommodating a modern national high-speed network without massive, expensive, and permanently constraining underground intervention.

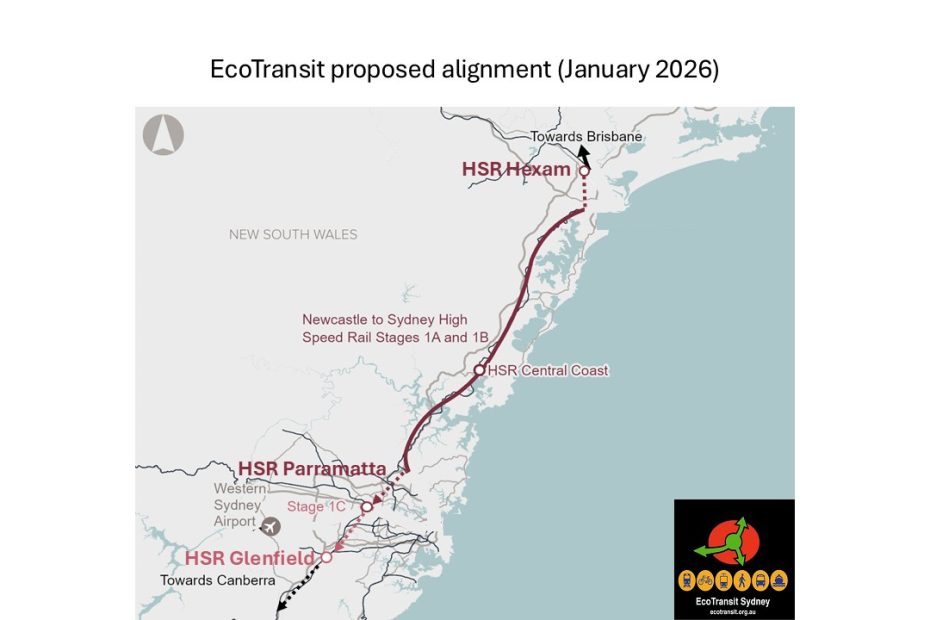

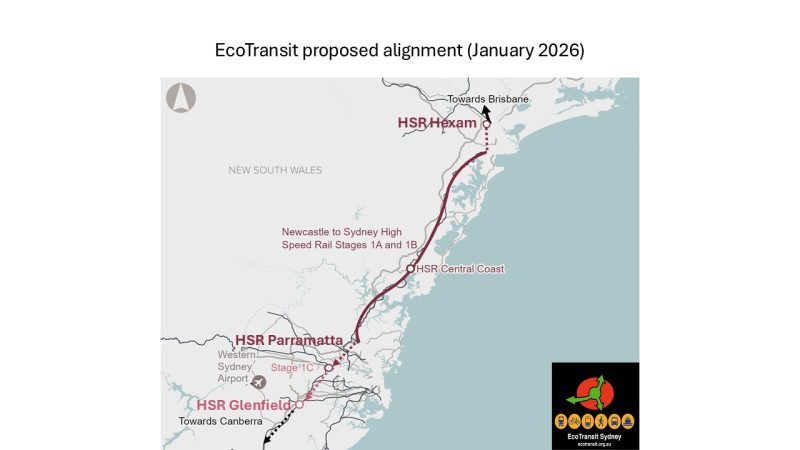

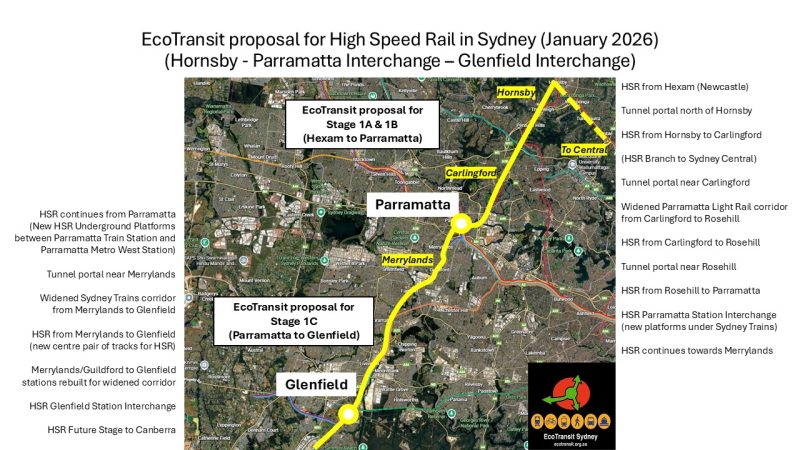

EcoTransit’s position remains unequivocal: Parramatta must become Sydney’s primary high-speed rail interchange.

Parramatta offers land, scalability, network integration, future-proof geometry, and direct strategic access to Western Sydney International Airport. More importantly, it allows the national network to form around a coherent north–south high-speed axis, with east–west metropolitan services intersecting it — precisely the structure seen in successful global cities.

Persisting with Sydney Central as the sole anchor of the network guarantees decades of congestion, compromised performance, and avoidable cost escalation.

Reframing the Network: Canberra First, Newcastle Right

A fundamental structural error in the current high-speed rail program is the assumption that Sydney–Newcastle must be the first corridor to be delivered. From a national network, economic and engineering perspective, the highest-value first stage is in fact Parramatta – Canberra, not Sydney – Newcastle. This is the corridor where high-speed rail delivers the greatest immediate productivity return, the strongest mode-shift from aviation, the lowest construction risk, and the clearest pathway to building a coherent national spine.

Parramatta–Canberra directly links Australia’s largest metropolitan labour market with the national capital — two of the country’s most powerful economic and institutional centres. It is the corridor where aviation dominance is weakest and where rail’s competitiveness threshold is easiest to exceed. A true high-speed connection between Parramatta and Canberra would immediately transform intercity travel behaviour, delivering journey times capable of capturing most of the existing air market while catalysing decentralisation of the public service, regional housing supply growth and economic development across the Southern Tablelands.

Critically, the Parramatta–Canberra alignment also avoids the extreme tunnelling burden that now cripples the Sydney–Newcastle proposal. The topography of the Southern Highlands and Tablelands corridor allows for a far higher proportion of surface and viaduct construction, enabling sustained 300–350 km/h operation across most of the route at dramatically lower cost and risk. This allows Australia’s first high-speed rail line to demonstrate genuine global performance from day one — building technical credibility, public confidence and investor support for the broader national rollout.

At the southern end of this trunk, the existing Canberra–Cooma railway corridor should be fully reopened, electrified and upgraded to operate as a lower-speed high-speed extension, delivering fast electric services around 160km/h into the Snowy Mountains region. This would immediately transform access to the Snowy for tourism, workforce mobility, freight resilience and emergency response, while integrating seamlessly with the national high-speed spine.

At the northern end of the future network, the same strategic discipline must apply. Rather than forcing true high-speed operations into the constrained geometry of the existing Newcastle city terminus, Hexham should be established as the functional “Newcastle” high-speed rail interchange. Hexham offers superior alignment geometry, extensive land availability, and direct integration with the Hunter Line linking Newcastle CBD and the broader regional rail network. This would allow the high-speed mainline to maintain optimal alignment and sustained speed, while distributing passengers efficiently into Newcastle, Maitland, Cessnock, Singleton and the Upper Hunter.

This must be paired with the full electrification and modernisation of the Hunter Line, creating a high-capacity, high-frequency electric regional network feeding the high-speed spine — precisely the operating model used by the world’s most successful rail systems.

The strategic logic is clear and internationally proven:

First build the trunk. Then connect the regions properly.

If Australia is serious about building a world-class high-speed rail system, the first kilometre should not be poured north of Sydney.

It should be laid between Parramatta and Canberra.

Conclusion: Build It Right, Or Lock in Failure

High-speed rail is not a transport project. It is nation-shaping economic infrastructure whose design will govern Australia’s productivity, competitiveness, sustainability, and spatial development for the next century.

If Sydney–Newcastle is built as currently proposed, Australia will inherit a railway that is slower, more expensive, and more constrained than global best practice demands — and those deficiencies will be locked into the national system permanently. No future government, no future budget and no future technological advance will be able to correct them.

Australia still has time to change course.

But the moment concrete is poured, the moment tunnels are bored, the moment geometry is fixed, the future is sealed.

This is the last point at which Australia can choose between a world-class high-speed rail network and a compromised experiment that will burden the nation for generations.

We must choose wisely.